W 2025 roku konflikty zbrojne toczą się w kilku kluczowych regionach świata. Oto niektóre z najbardziej znaczących obszarów:

Ukraina: Wojna z Rosją trwa nadal, z eskalacją działań wojennych i różnymi prognozami dotyczącymi możliwego zakończenia konfliktu. Rosja zwiększa wydatki na obronę, co sugeruje przygotowania do dalszej eskalacji lub przedłużenia konfliktu.

Bliski Wschód: Sytuacja na Bliskim Wschodzie pozostaje niestabilna, z szczególnym naciskiem na działania Izraela w Gazie, na Zachodnim Brzegu, oraz potencjalne konflikty z Libanem i Syrią.

Azja Wschodnia: Wokół Tajwanu trwają napięcia, z możliwą eskalacją konfliktu z Chinami, które mogą prowadzić do blokady tego regionu.

Półwysep Koreański: Istnieje ryzyko wybuchu wojny, zwłaszcza w kontekście potencjalnych działań wojskowych USA w Meksyku, które mogą mieć pośredni wpływ na region.

Ponadto, konflikty mniej nagłośnione w mediach, ale nadal trwające, obejmują różne części świata, takie jak Afganistan, Jemen, i Syria, gdzie walki mogą mieć charakter lokalny, ale są częścią większych geopolitycznych napięć.

Afganistan: Po wycofaniu się NATO w 2021 roku, kraj zmaga się z wewnętrznymi napięciami i walkami między talibami a różnymi grupami opozycyjnymi.

Jemen: Konflikt zbrojny trwa od 2014 roku, z interwencją Arabii Saudyjskiej i walkami między Huti a rządem.

Syria: Wojna domowa, która rozpoczęła się w 2011 roku, wciąż trwa, mimo zamrożenia niektórych frontów

Warto również zauważyć, że te informacje odzwierciedlają sytuację na podstawie aktualnych prognoz i doniesień z 2025 roku, co może podlegać zmianom wraz z rozwojem sytuacji międzynarodowej.

Zamiast podporządkowywać się Zachodowi czy Wschodowi, te kraje prowadzą własną grę, kierując się pragmatyzmem i interesem narodowym.

Indie – kupują tanią ropę od Rosji, milczą w ONZ, negocjują zbrojenia.

Arabia Saudyjska i ZEA – balansują między USA, Rosją i Chinami.

Turcja – wspiera Ukrainę, blokuje NATO, handluje z Rosją.

BRICS – przekształca się w platformę antyhegemoniczną, promując rozliczenia w lokalnych walutach i własne instytucje.

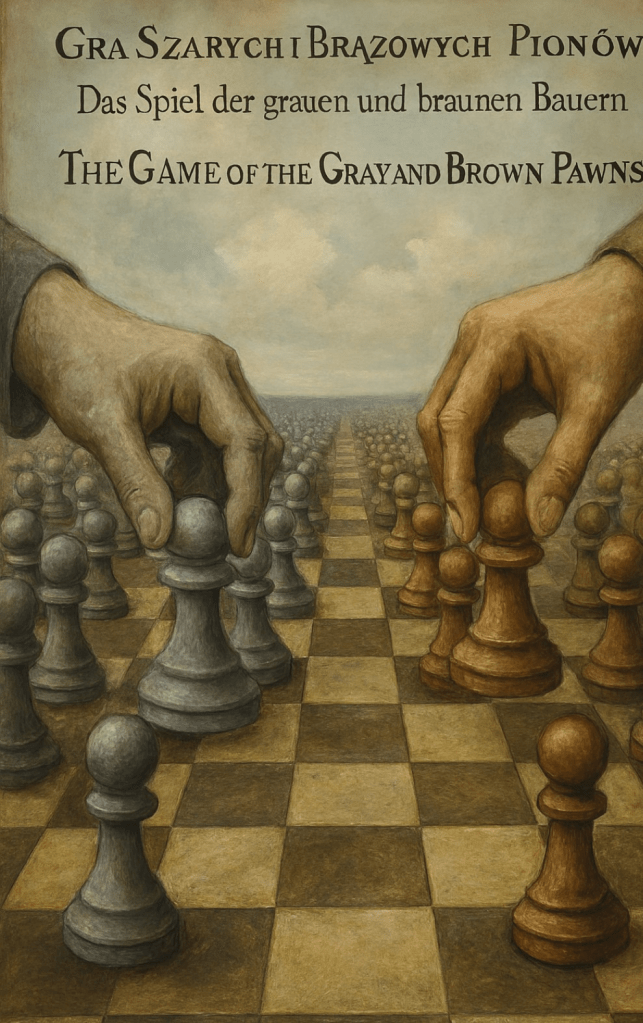

GRA SZARYCH I BRĄZOWYCH PIONÓW

Płonęły mosty, które miały być wieczne. Waszyngton, Bruksela, Moskwa, Pekin – każde z tych centrów władzy wierzyło, że ich szachownica jest tą jedyną, a ruchy przeciwnika da się przewidzieć. Ale prawdziwa gra toczyła się gdzie indziej. Na południe od ich starych podziałów, w stolicach, które Zachód nazywał „rozwijającymi się”, a które właśnie dojrzewały do roli architektów nowego świata.

To nie była partia szachów między Białymi a Czarnymi. To była gra, w której Szare i Brązowe piony ożyły.

W New Delhi, pod palącym słońcem, urzędnicy chłodno kalkulowali. Ceny rosyjskiej ropy spadły drastycznie. Dlaczego mieliby płacić więcej, zaciągać się długami i zrywać relacje z jednym partnerem, tylko by zadowolić drugiego? Zachód mówił o zasadach, ale Indie myślały o rozwoju. Kupowali tanią ropę, negocjowali zbrojenia, milczeli w ONZ. To nie była zdrada. To była suwerenna decyzja. Byli graczem, nie nagrodą.

Tysiące kilometrów dalej, w pałacach Rijadu i Abu Zabi, inny spektakl był w toku. Królowie i szejkowie przyjmowali zarówno amerykańskich generałów, jak i rosyjskich handlarzy bronią oraz chińskich inwestorów. Byli sojusznikami USA, ale ich bezpieczeństwo budowali na wielu filarach. Inwestowali w Rosję, wchodzili w BRICS, prowadzili własną grę. Ich lojalność nie była do wzięcia – była do wynajęcia na korzystnych warunkach.

Ankara. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan patrzył na mapę. Jego drony leciały nad Ukrainą, wzmacniając jej obronę. Jednocześnie jego dyplomaci blokowali rozszerzenie NATO, a jego biznesmeni kwitli na handlu z Rosją. Turcja nie wybierała stron. Wykorzystywała konflikt, by stać się niezbędnym dla wszystkich. Była bramą, strażnikiem, pośrednikiem. Była nieprzewidywalna, a przez to niezastąpiona.

W Afryce i Azji Południowej echa zachodnich nawoływań o solidarność odbijały się echem od murów obojętności. Sankcje? Widziano je jako kolejne narzędzie neokolonialnej presji. Pomoc humanitarna? Przyjmowano ją z wdzięcznością, ale bez zobowiązań. Te kraje pamiętały długi, narzucone warunki, protekcjonalne tonacje. Teraz miały wybór. I wybierały własny interes.

To nie był chaos. To byly narodziny nowego porządku.

Klub BRICS, dawniej ciekawostka dla ekonomistów, teraz rozrastał się w platformę antyhegemoniczną. Nie chodziło o to, by zastąpić Zachód nowym imperium, ale by odebrać mu monopol na tworzenie reguł. Rozliczenia w lokalnych walutach, własne banki rozwoju, własne forum bezpieczeństwa – to były narzędzia dekonstrukcji. Świat nie dzielił się już na sojusze. Dzielił się na transakcje.

Zachód, oszołomiony, próbował nadążyć. Jego sankcje, niegdyś miażdżąca broń, przeciekały jak sito. Jego moralizatorski język napotykał na mur pragmatyzmu. Powoli, z oporami, uczył się nowej gramatyki władzy: nie nakazywać, lecz proponować; nie pouczać, lecz słuchać; nie żądać lojalności, lecz na nią zapracować.

Prawdziwa gra nie toczyła się już na froncie w Ukrainie. Toczyła się w gabinetach Nowego Delhi, Rijadu, Ankary, Pretorii. To tam decydowano, czyja wizja świata zyska globalną legitymizację. To tam rozstrzygał się kształt przyszłości.

Epoka wielobiegunowości nadeszła nie jako teoretyczna koncepcja, ale jako fakt. Jej architektami nie były mocarstwa, które wciąż tkwiły w starym myśleniu o blokach. Były nią kraje Globalnego Południa – owe „szare i brązowe” piony, które odmówiły bycia jedynie tłem dla czyjejś gry. Ożyły, by stworzyć własną.

I to one, właśnie teraz, pisały nowe reguły.

DAS SPIEL DER GRAUEN UND BRAUNEN BAUERN

Die Brücken, die ewig sein sollten, brannten. Washington, Brüssel, Moskau, Peking – jedes dieser Machtzentren glaubte, dass sein Schachbrett das einzig Wahre sei und die Züge des Gegners vorhersehbar wären. Aber das wahre Spiel fand woanders statt. Südlich ihrer alten Trennlinien, in Hauptstädten, die der Westen als „Entwicklungsländer“ bezeichnete und die gerade dabei waren, zu den Architekten einer neuen Welt heranzureifen.

Es war keine Schachpartie zwischen Weiß und Schwarz. Es war ein Spiel, in dem die grauen und braunen Figuren zum Leben erwachten.

In Neu-Delhi kalkulierten Beamte unter der brennenden Sonne nüchtern. Die Preise für russisches Öl waren drastisch gefallen. Warum sollten sie mehr zahlen, Schulden aufnehmen und die Beziehungen zu einem Partner abbrechen, nur um einen anderen zufriedenzustellen? Der Westen sprach von Prinzipien, aber Indien dachte an Entwicklung. Sie kauften billiges Öl, verhandelten über Rüstungsgeschäfte, schwiegen in der UNO. Das war kein Verrat. Es war eine souveräne Entscheidung. Sie waren ein Spieler, nicht ein Preis.

Tausende Kilometer entfernt, in den Palästen von Riad und Abu Dhabi, fand ein anderes Schauspiel statt. Könige und Scheichs empfingen sowohl amerikanische Generäle als auch russische Waffenhändler und chinesische Investoren. Sie waren Verbündete der USA, aber ihre Sicherheit bauten sie auf mehreren Säulen auf. Sie investierten in Russland, traten den BRICS bei, spielten ihr eigenes Spiel. Ihre Loyalität war nicht zu haben – sie war zu mieten, und zwar zu günstigen Konditionen.

Ankara. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan betrachtete die Karte. Seine Drohnen flogen über die Ukraine und stärkten ihre Verteidigung. Gleichzeitig blockierten seine Diplomaten die NATO-Erweiterung, und seine Geschäftsleute blühten im Handel mit Russland auf. Die Türkei wählte keine Seiten. Sie nutzte den Konflikt, um für alle unverzichtbar zu werden. Sie war das Tor, der Wächter, der Vermittler. Sie war unberechenbar und damit unersetzlich.

In Afrika und Südasien verhallten die westlichen Aufrufe zur Solidarität an Mauern der Gleichgültigkeit. Sanktionen? Sie wurden als ein weiteres Instrument neokolonialen Drucks angesehen. Humanitäre Hilfe? Man nahm sie dankbar an, aber ohne Verpflichtungen. Diese Länder erinnerten sich an Schulden, auferlegte Bedingungen, bevormundende Töne. Jetzt hatten sie eine Wahl. Und sie wählten ihr eigenes Interesse.

Das war kein Chaos. Es war die Geburt einer neuen Ordnung.

Der BRICS-Club, einst eine Kuriosität für Ökonomen, wuchs nun zu einer antihegemonialen Plattform heran. Es ging nicht darum, den Westen durch ein neues Imperium zu ersetzen, sondern ihm das Monopol der Regelgebung zu entziehen. Abrechnungen in Landeswährungen, eigene Entwicklungsbanken, eigene Sicherheitsforen – das waren die Werkzeuge der Dekonstruktion. Die Welt teilte sich nicht mehr in Bündnisse. Sie teilte sich in Transaktionen.

Der Westen, benommen, versuchte Schritt zu halten. Seine Sanktionen, einst eine vernichtende Waffe, leckten wie ein Sieb. Seine moralisierende Sprache stieß auf eine Mauer des Pragmatismus. Langsam, widerstrebend, lernte er eine neue Grammatik der Macht: nicht befehlen, sondern vorschlagen; nicht belehren, sondern zuhören; nicht Loyalität fordern, sondern sie verdienen.

Das wahre Spiel fand nicht mehr an der Front in der Ukraine statt. Es fand in den Büros von Neu-Delhi, Riad, Ankara und Pretoria statt. Dort wurde entschieden, wessen Weltvision globale Legitimität erlangen würde. Dort wurde die Gestalt der Zukunft entschieden.

Die Ära der Multipolarität war nicht als theoretisches Konzept, sondern als Fakt angebrochen. Ihre Architekten waren nicht die Großmächte, die im alten Denken in Blöcken steckengeblieben waren. Es waren die Länder des Globalen Südens – jene „grauen und braunen“ Figuren, die sich weigerten, nur die Kulisse für das Spiel eines anderen zu sein. Sie waren zum Leben erwacht, um ihr eigenes zu erschaffen.

Und sie waren es, die jetzt die neuen Regeln schrieben.

THE GAME OF THE GRAY AND BROWN PAWNS

The bridges that were meant to be eternal were burning. Washington, Brussels, Moscow, Beijing—each of these power centers believed that their chessboard was the only one, and that their opponent’s moves could be predicted. But the real game was being played elsewhere. South of their old divisions, in capitals that the West called “developing,” but which were now coming of age as the architects of a new world.

This was not a chess match between White and Black. This was a game in which the Gray and Brown pieces came to life.

In New Delhi, under the scorching sun, officials calculated coldly. The price of Russian oil had plummeted. Why should they pay more, incur debts, and sever ties with one partner just to please another? The West spoke of principles, but India thought of development. They bought cheap oil, negotiated arms deals, remained silent at the UN. This was not betrayal. It was a sovereign decision. They were players, not prizes.

Thousands of kilometers away, in the palaces of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, a different spectacle was unfolding. Kings and sheikhs hosted American generals, Russian arms dealers, and Chinese investors alike. They were allies of the US, but they built their security on multiple pillars. They invested in Russia, joined BRICS, played their own game. Their loyalty was not for the taking—it was for rent, on favorable terms.

Ankara. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan looked at the map. His drones flew over Ukraine, strengthening its defense. At the same time, his diplomats blocked NATO expansion, and his businessmen thrived on trade with Russia. Turkey did not choose sides. It leveraged the conflict to become indispensable to everyone. It was a gateway, a guardian, an intermediary. It was unpredictable, and thus irreplaceable.

In Africa and South Asia, echoes of Western calls for solidarity bounced off walls of indifference. Sanctions? They were seen as just another tool of neocolonial pressure. Humanitarian aid? It was accepted with gratitude, but without commitments. These nations remembered debts, imposed conditions, patronizing tones. Now they had a choice. And they chose their own interest.

This was not chaos. It was the birth of a new order.

The BRICS club, once a curiosity for economists, was now expanding into an anti-hegemonic platform. The goal was not to replace the West with a new empire, but to strip it of its monopoly on rule-making. Settlements in local currencies, their own development banks, their own security forums—these were the tools of deconstruction. The world was no longer divided into alliances. It was divided into transactions.

The West, stunned, tried to keep up. Its sanctions, once a crushing weapon, now leaked like a sieve. Its moralizing language met a wall of pragmatism. Slowly, reluctantly, it was learning a new grammar of power: not to command, but to propose; not to lecture, but to listen; not to demand loyalty, but to earn it.

The real game was no longer being played on the frontlines in Ukraine. It was being played in the offices of New Delhi, Riyadh, Ankara, Pretoria. It was there that it was decided whose vision of the world would gain global legitimacy. It was there that the shape of the future was being determined.

The era of multipolarity had arrived not as a theoretical concept, but as a fact. Its architects were not the great powers still stuck in the old thinking of blocs. They were the countries of the Global South—those “gray and brown” pieces that refused to be mere background for someone else’s game. They had come to life to create their own.

And it was they, right now, who were writing the new rules.

📚 Bibliografia:

Zmiana Paradygmatu: Koniec Hegemoni i Narodziny Wielobiegunowości

Acharya, A. (2018). The End of American World Order (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

Kupchan, C. A. (2012). No One’s World: The West, The Rising Rest, and The Coming Global Turn. Oxford University Press.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2019). Bound to Fail: The Rise and Fall of the Liberal International Order. International Security, 43(4), 7–50.

Zakaria, F. (2008). The Post-American World. W.W. Norton & Company.

Praktyczny Pragmatyzm: Studia Przypadków

a) Indie: Suwerenna Kalkulacja

Jaishankar, S. (2020). The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World. HarperCollins India.

Pant, H. V., & Super, J. (2023). India and the Ukraine War: A New Chapter in Strategic Autonomy? The Washington Quarterly, 46(2), 167–185.

Reuters. (2023). India’s Russian Oil Imports [Seria artykułów analitycznych]. Pobrane z https://www.reuters.com/ (dostęp: 10.09.2025).

b) Kraje Zatoki Perskiej: Wielowektorowość

Davidson, C. M. (2023). From Dependency to Multipolarity: The New Foreign Policy of the Gulf States. Hurst & Company.

Guzansky, Y., & Even, S. (2021). The Arab World between the Hammer of the United States and the Anvil of China. INSS Strategic Assessment.

Kamrava, M. (2020). Pragmatism over Ideology: Iran and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in a Changing Middle East. Georgetown University School of Foreign Service in Qatar.

c) Turcja: Strategia „Pośrednika”

Taşpınar, Ö. (2022). Erdogan’s Empire: Turkey and the Politics of the New Middle East. I.B. Tauris.

İdiz, S. (2022, 15 grudnia). Is Turkey’s „Balancing Act” Between Russia and the West Sustainable? Carnegie Europe. Pobrane z https://carnegieeurope.eu/ (dostęp: 10.09.2025).

Kirisci, K., & Özcan, M. (2022). Turkey’s Drone Strategy: A Game Changer in Military Doctrine and Foreign Policy. Turkish Policy Quarterly, 21(2).

BRICS i Instytucjonalna Dekonstrukcja

Stuenkel, O. (2016). Post-Western World: How Emerging Powers Are Remaking Global Order. Polity Press.

Abdenur, A. E., & Folly, M. (2023). The New Development Bank and the Contingencies of Southern-Led Cooperation. Global Policy.

BRICS Information Centre. (n.d.). Academic resource with official documents and analyses. Pobrane z https://brics.utoronto.ca/ (dostęp: 10.09.2025).

Krytyka Zachodu i Perspektywa Globalnego Południa

Mishra, P. (2012). From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Shankar, S. (2023). The Revenge of the Global South: Why the Rest is Resisting the West’s Rules. Foreign Affairs.

Ahmad, A. (2023, 10 marca). The Ukraine War and the Rest of the World. The New Yorker. Pobrane z https://www.newyorker.com/ (dostęp: 10.09.2025).

Sankcje i Ich Skuteczność

Drezner, D. W. (2021). The United States of Sanctions: The Use and Abuse of Economic Coercion. Foreign Affairs.

International Monetary Fund. (2023). World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery. Rozdział: „The Geoeconomic Fragmentation”. Pobrane z https://www.imf.org/ (dostęp: 10.09.2025).

Even, S. (2022). Circumventing Sanctions: How Russia and Its Partners Are Adapting. INSS Insight No. 1658.

Główne źródła kontekstowe (artykuły analityczne i doniesienia medialne):

Indie a wojna na Ukrainie

The Economist. Why India is stocking up on Russian oil.

Reuters. India becomes top buyer of Russian sea-borne oil as China takes back seat.

Bloomberg. India’s Russian Oil Imports Jump to Record on Cheap Prices.

Wielowektorowa polityka krajów Zatoki Perskiej

Foreign Affairs. The Middle East’s New Great Game.

The Wall Street Journal. Saudi Arabia’s New Oil Strategy: Less Western, More Global.

CNBC. Saudi Arabia joins China-led security bloc as ties with US fray.

Pozycja Turcji jako mediator

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Turkey’s Hard Power Play in Ukraine.

Politico. Erdogan plays NATO off against Russia in high-stakes balancing act.

BRICS i Globalne Południe

Chatham House. What does the expansion of BRICS mean for the world order?

Financial Times. Brics nations plan new currency to challenge dollar dominance.

Le Monde diplomatique (edycja polska). Bunt Globalnego Południa.

Kryzys sankcji zachodnich

International Monetary Fund (IMF). Sanctions Fragmenting the Global Economy.

The Guardian. Western sanctions on Russia are failing, study suggests.

Uwaga metodologiczna:

Powyższa bibliografia łączy prace akademickie formułujące ramy teoretyczne, analizy think tanków oraz wiarygodne artykuły medialne dokumentujące aktualne geopolityczne i ekonomiczne wydarzenia.